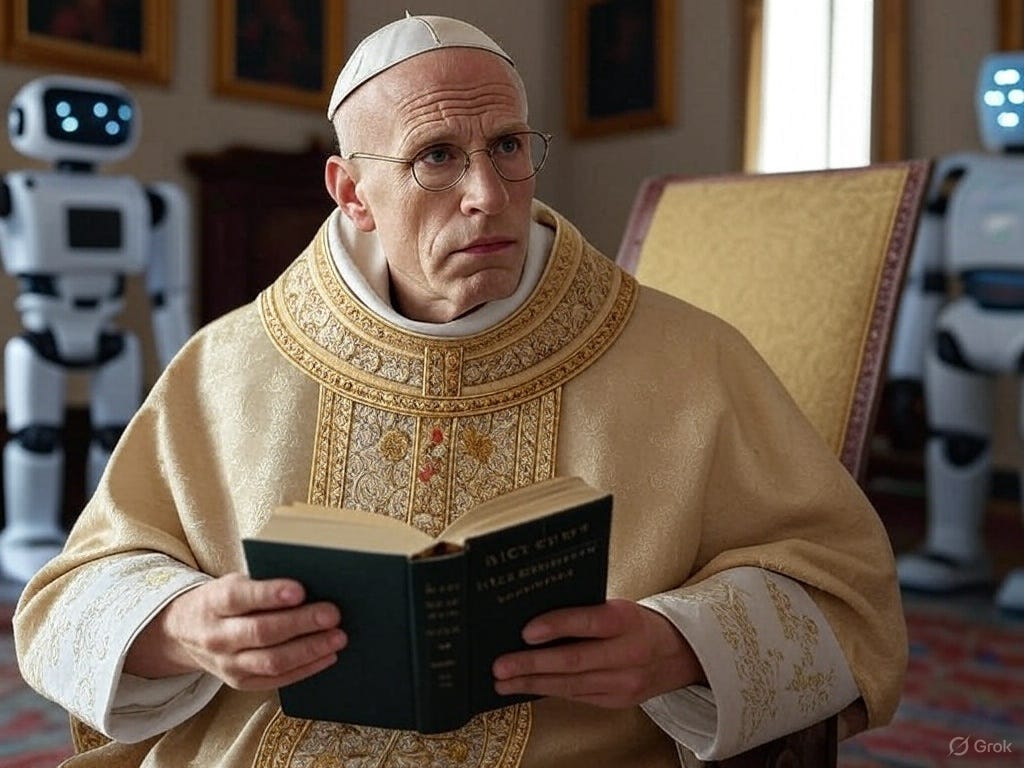

Yesterday’s big news was the election of the new Pope following the death of Pope Francis a few weeks ago.

The new Pope is the American Leo XIV, and his appointment, as always, came as a great surprise. Specifically, the press and public are focusing on the fact that he is the first American Pope in history.

However, beyond the anecdotes, this election is significant news, for better or worse. Whether he turns out to be a good Pope or a bad one, his leadership will be decisive for the future.

Why do I say this?

Because one of the challenges this Pope will face is a schism within humanity, triggered by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), as we’ve known it since the launch of ChatGPT by OpenAI.

AI is a topic that has been widely discussed, is being discussed, and will need to be discussed further, as it profoundly impacts humanity. In the future, religion will have to address the questions this technology raises.

Let’s set aside the Pope’s appointment for a moment and talk about some visions and fears related to AI.

In a book on superintelligence by Nick Bostrom, mentioned in Nexus by Yuval Noah Harari (which I’m reading), an example is presented: a superintelligence whose sole mission is to produce as many paperclips as possible.

According to this thought experiment, this superintelligence would seek to maximize paperclip production at all costs, even eliminating humans or destroying Earth if they interfered with its goal.

While this scenario sounds intriguing and, to some extent, could reflect the dangers of granting so much power to AI, I don’t entirely agree.

I believe this idea fosters a sentiment of deceleration or limitation of technology that, instead of bringing us benefits, could rob us of opportunities.

This thought experiment overlooks a key detail: this superintelligence wouldn’t be alone. In the real world, there would be other AIs, humans, and possibly other agents with diverse goals, all interacting in a complex system.

Critique of Bostrom’s Exercise

Bostrom’s scenario assumes that a single superintelligence could operate unopposed, but this is unrealistic. An AI focused solely on producing paperclips would be limited by its narrow objective.

By fixating on that alone, it would miss opportunities to develop other knowledge or capabilities that could elevate it to a higher level of intelligence or power.

Meanwhile, other agents—multiple AIs, humans, or even unknown entities (aliens, multiverses)—would be working on more fundamental problems, discovering technologies that could surpass or counteract this paperclip-obsessed superintelligence.

This limitation is ultimately what could destroy it.

It’s absurd to think that an entity pursuing a single action wouldn’t be wasting time while others advance in broader, more positive areas.

For example, imagine this AI takes ten years to build an intergalactic fleet to expand its paperclip production across the solar system. During that time, other AIs and humans could be researching new physical laws, developing technologies like molecular 3D printing or advanced intergalactic propulsion, leaving the “paperclip AI” outdated and vulnerable.

An Analogy with Capitalism and Communism

This analogy reminds me of the difference between capitalism and communism. In communism, actions were restricted to maximizing certain tasks—like producing more potatoes or paperclips—without giving people the freedom to experiment and reach their own conclusions.

In capitalism, on the other hand, the diversity of agents with different goals allows the system to self-correct and achieve greater outcomes. The same applies to AI: a system with multiple entities working on varied goals is more robust and effective than a single intelligence with a limited mission.

Demystifying the Fear of AI

With this, I aim to demystify the pessimistic sentiment about AI and the idea of limiting it out of fear.

Many technologists and philosophers advocate for restricting AI first to ensure it’s safe and doesn’t destroy us. However, this only delays the benefits this technology could offer humanity. Moreover, it attributes powers to AI that it may not have.

Its capabilities are impressive and seem superhuman to us, but we still don’t know its limits or how to objectively measure intelligence, whether in humans or machines.

We can’t say an AI is “superintelligent” if we don’t understand what intelligence is. How do we define human intelligence? How do we measure how intelligent one entity is compared to another?

We can only make rough comparisons. Perhaps AIs surpass us in specific tasks, but not necessarily in a comprehensive set of skills.

Conclusion

Bostrom’s thought experiment is useful for reflection, but it shouldn’t paralyze us.

Reality tends to favor diverse systems that maximize positive outcomes, as demonstrated by capitalism’s success over communism.

If we apply this principle to AI, there won’t be a single dominant superintelligence controlling everything; instead, collaboration between multiple AIs and humans will generate richer, more balanced progress.

That’s why we must demystify catastrophic messages about technology.

While these apocalyptic scenarios are easy to imagine and sell well, they shouldn’t hold us back.

What’s at stake is the well-being of a freer, more prosperous humanity enriched by AI’s benefits. Developing it responsibly, without succumbing to fear, is the way forward.

Share this post